I shuffled across the room like I needed a walker and surgery this morning. I rolled into the park later than I’d intended, and headed over to Panther Junction for a shopping trip:

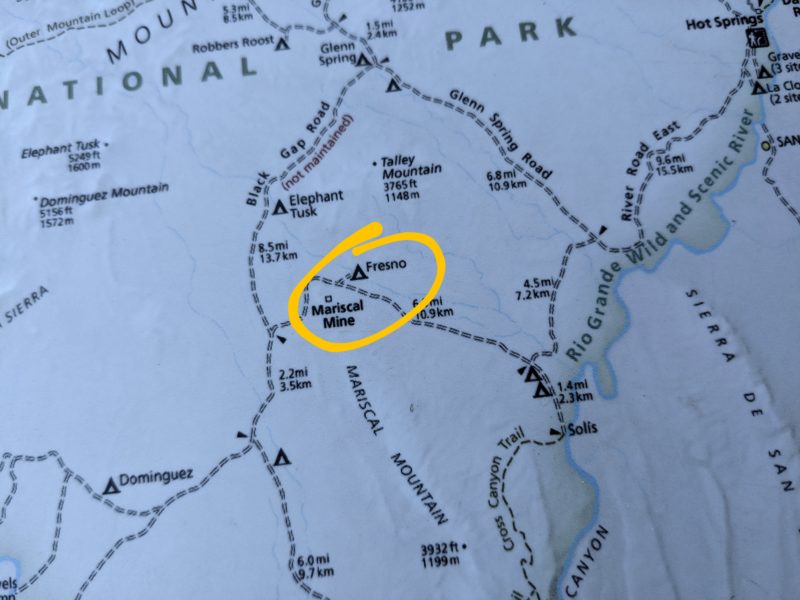

I also picked up a backroads guidebook written by the Big Bend National History Association. I already have topo maps and track routes saved for every backroad in the park, but this $4 pamphlet includes a lot of backstory generally, and especially a lot about the Mariscal Mine that we discovered in 2018. Relatedly, I stopped by the ranger’s desk and asked if there had been any cancellations for backroads campsites. As luck would have it, the Ranger offered me Fresno:

It meant that my campsite was only a third of the way across River Road, leaving two thirds of that plus the drive to Austin for Sunday, but that’s Sunday’s problem. I’d be camping at an abandoned mine tonight! And I suddenly had an entire afternoon to pass slowly. But that felt like my speed for today. I started with a short hike at Boquillas Canyon, downriver at the east end of the park.

Boquillas del Carmen is a small village on the Mexico side of a foot-traffic-only border crossing inside the park. Unfortunately, the crossing has been closed for COVID-19, shutting down the incredibly remote town’s primary revenue source. I saw more souvenir “stores” than usual along the trails and overlooks around the canyon — a small collection of handmade crafts perched on a boulder with a pricelist and cash jar. For my part, I did a little more shopping.

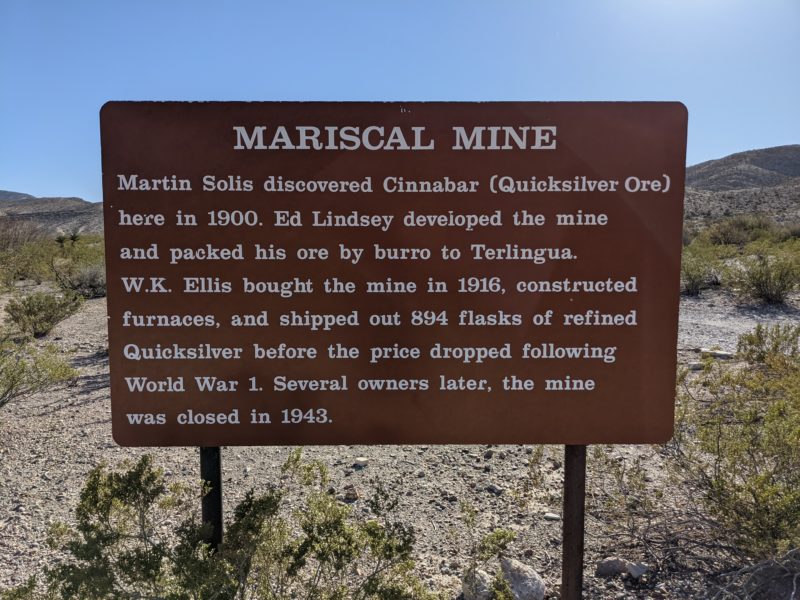

After my river stroll, I started the River Road drive and arrived at the Mariscal Mine much sooner than I expected.

Cinnabar, the ore extracted here, is the brick-red form of mercury(II) sulfide (HgS). It is the most common source ore for refining elemental mercury and the historic source for the brilliant red or scarlet pigment called vermilion. The mercury produced here was used in various drugs, chemicals, and explosives detonators. Ore was discovered here in 1900 but mining didn’t start until a few years later. Refining buildings weren’t added until 1916. Early owners packed out their ore on mules to the furnaces in Terlingua.

According to my new book, the mine shipped out 894 flasks of quicksilver, each weighing 76 pounds. After World War I and a price drop in quicksilver, then-owner W. K. Ellis sold his holdings to the Mariscal Mining Company which continued operations until 1923 when the mine closed functionally but was still held on paper. A few transfers later, an additional 97 flasks of quicksilver were extracted in 1942 and 1943 by new owners, but then the mine went inactive for good.

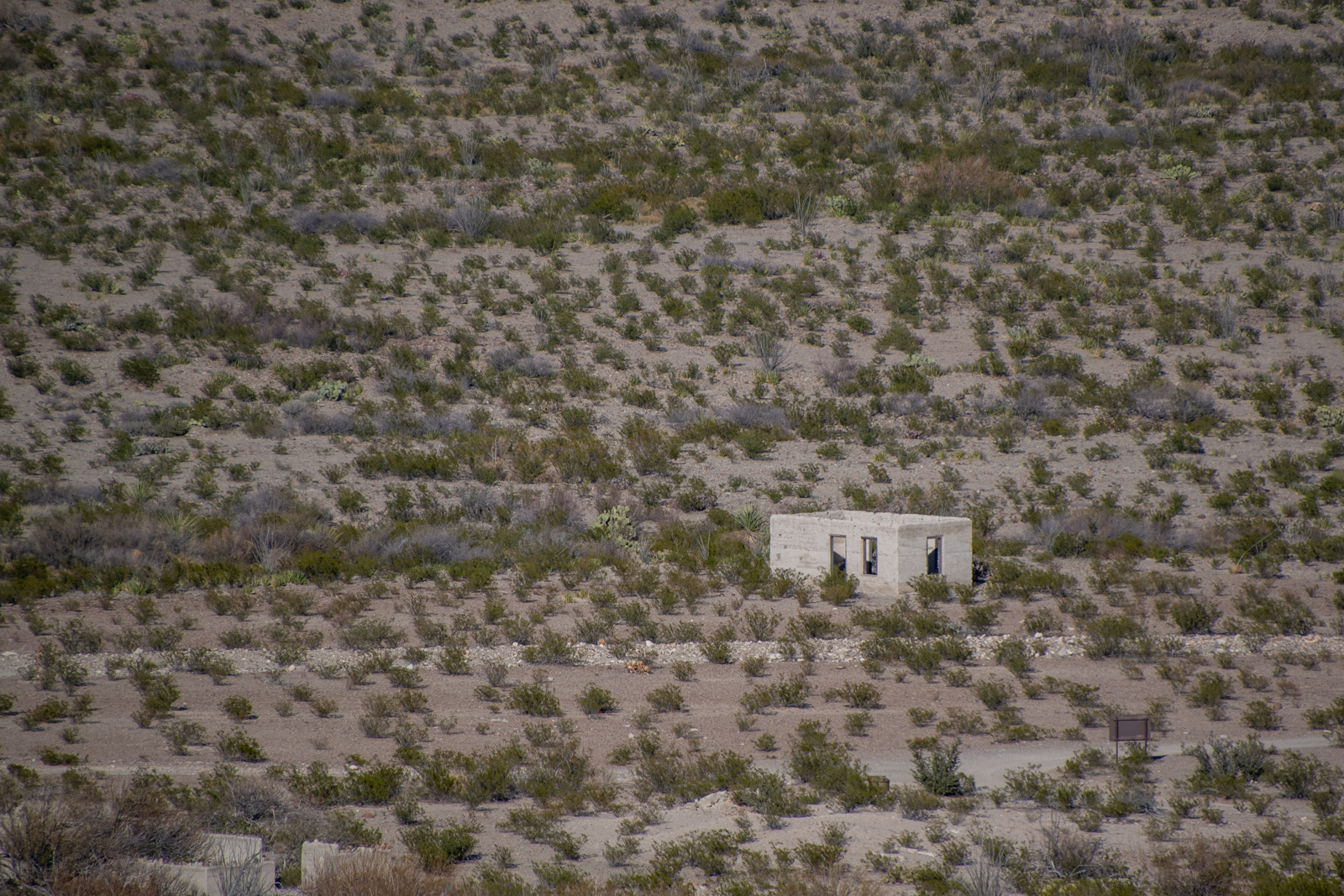

“Sit and don’t do much” isn’t usually part of my daily life or travel itineraries. But after a few minutes of feeling like I should be on the move, I sat on the edge of the old blacksmith shop and quietly watched the daylight fade over a beer.

I wandered back to the car for dinner and photo editing while I waited for nightfall. I wanted to head back to the mine and photograph it at night. But as it got darker, I could feel the ghosts watching. And I’ll reluctantly admit — I was intimidated. I didn’t want to be eaten by monsters or fall into a haunted mineshaft.

I decided I should practice my night photography on the housing and company store ruins along the main road because something about being near the Xterra made me feel safer. Likely the combination of lockable steel doors and a sleeping bag to hide under.

But while I “practiced,” the last hints of sunlight faded to the west and a searing moonlight burst through the horizon. As it lit up the front of the house, I knew I had to go back to the mine. So I finished my bravery beer, grabbed a flashlight, put some music on my phone, and walked the half mile back up to the ruins.