Having left the idea to marinate, we each gravitated toward Oregon Trail as a trip theme after we tossed the idea around. And May seems as good a time as any to make the crossing. So we decided to make it happen. But that means we have a lot to do, with surprisingly little time until our little wagon train sets off. Thus begins the route planning.

A route vaguely following any of the historic Oregon Trail or Lewis and Clark expedition lines will be a stunningly scenic adventure. But this also gives us unique blend of not only American history but also computer history. Because — while we’ll source our routes, stops, and stories from many places — first thing’s first:

Why do we all know The Oregon Trail?

I’m speaking of the classic computer game, naturally. In its 2016 article, “How You Wound Up Playing ‘The Oregon Trail’ in Computer Class,” Smithsonian Magazine writes:

The Oregon Trail, Word Munchers, Storybook Weaver. All games you played in school, all made by the same state-funded company—the Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium. From 1978 to 1999, MECC, together with Apple, competed against private software companies to turn American children into a nation of computer-savvy early adopters and make computer class as much a part of American schooling as math and English. […] MECC’s goal was on putting a computer in the hands of every K-12 student in Minnesota. Once MECC had [its UNIVAC maintframe], it needed a game.

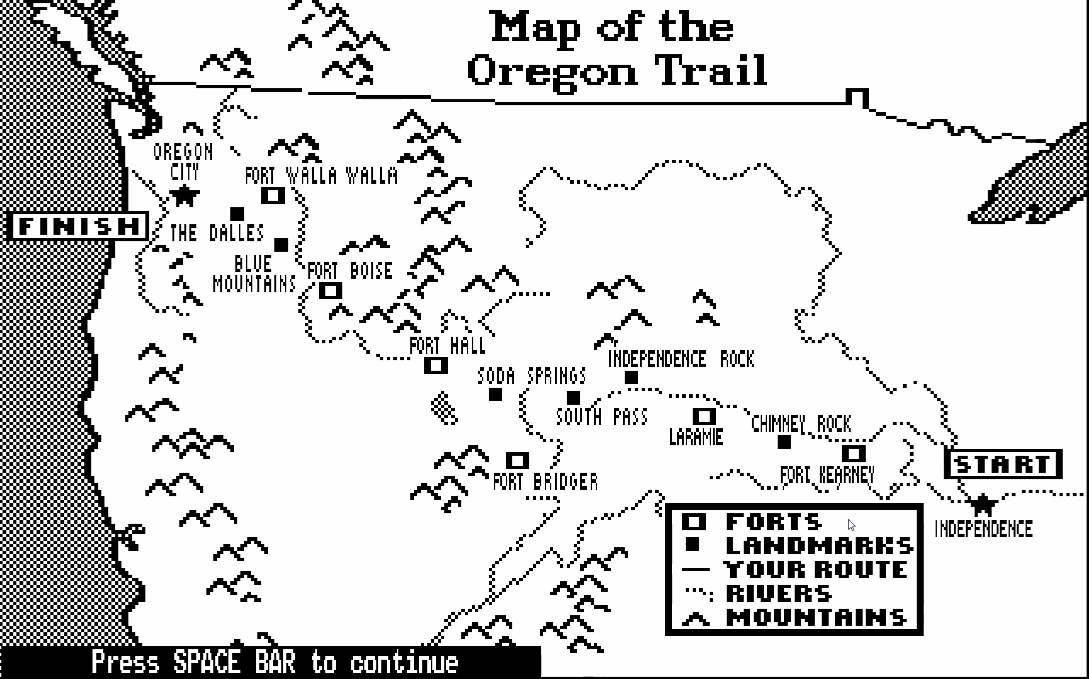

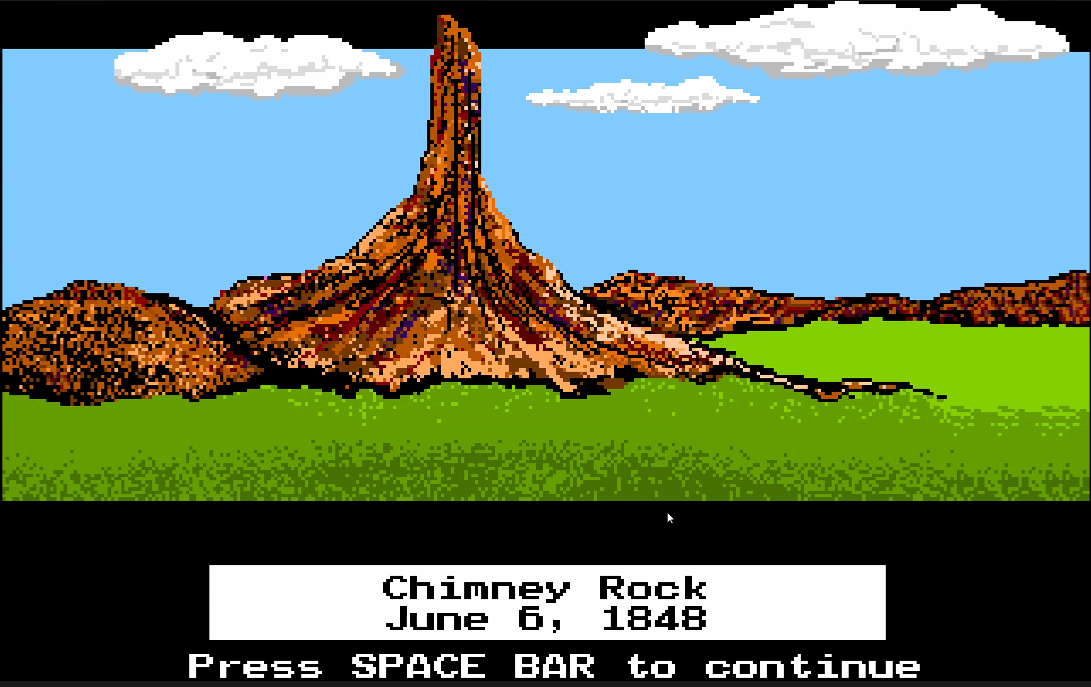

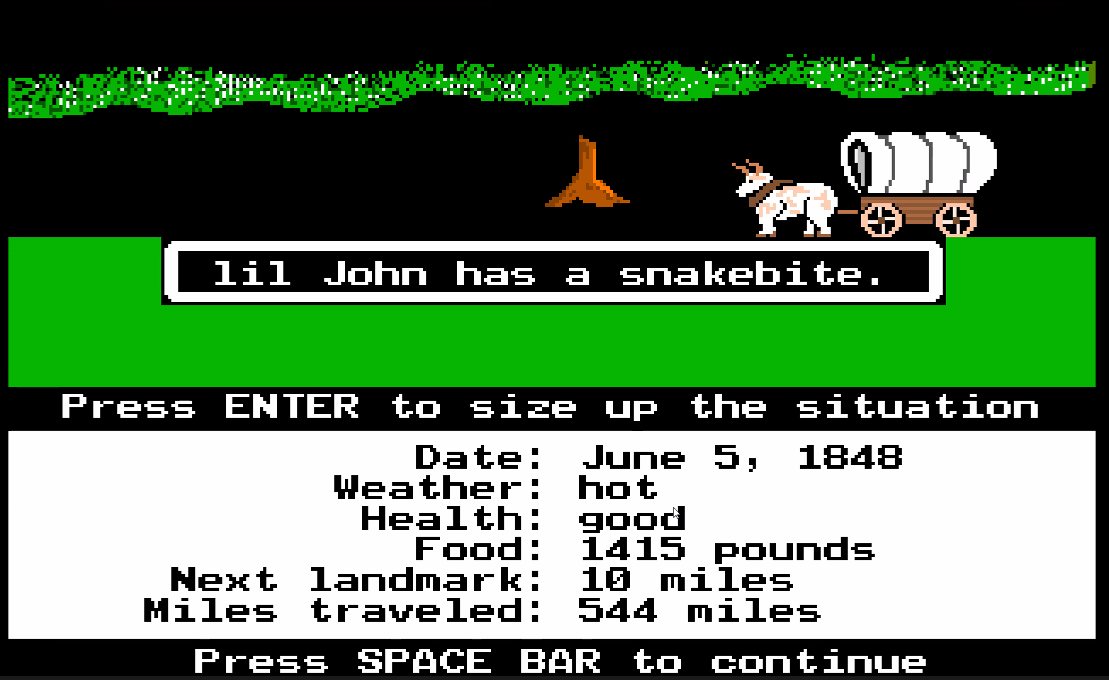

Don Rawitsch, Bill Heinemann and Paul Dillenberger, three student teachers enrolled at nearby Carleton College, created The Oregon Trail in November 1971 for an eighth-grade history class Rawitsch was teaching. The game starts in Missouri, 1848, where the player equips a party of pioneers for the 2,000-mile journey to Willamette Valley, Oregon. Along the way, the player manages his or her wagon train through river crossings, food shortages, injuries, illnesses, breakdowns and theft.”

Well if that doesn’t sound like the ideal place to get route planning inspiration, I don’t know what does.

When Rawitsch’s class ended, he removed the game from the mainframe — but printed out the source code (yes, on paper) before he did. MECC later hired him to resurrect the pile of papers, adding new features and plot points. He researched Oregon Trail pioneer diaries to help tie events and locations together. Some stories even mentioned help from Native tribes, which inspired him to add those encounters as well. The game was retooled and re-released multiple times as new generations of personal computers were created.

All MECC games had to do four things: First, the information based on real events had to be historically accurate. Second, learning couldn’t be spread out in patches; it had to be woven throughout the game start to finish. Third, it had to include thorough documentation for the teachers to use it as a teaching aid. And fourth, the games had to be fun.

Between 1975 and 1995, The Oregon Trail series was MECC’s most prolific title. Although MECC shut down after it was acquired, that game remains a cornerstone of “early experiences with computers” for many Gen X’ers and Millennials. The Internet is awash in reboots, parodies, and re-imaginings. And while we three weren’t as avid players as some of our peers, we remember this game and the ancient, table-sized computers that ran it in our early schools.

Thankfully, several organizations have managed to relaunch versions of the original to play in emulators online. We tried our luck on the 1990 PC-DOS release of The Oregon Trail courtesy of The Internet Archive.

Spoiler alert: one of us was killed at the hands of another.

Cutting this down from a slow-paced, alcohol-soaked 90 minute screenshare to a 22 minute super-rough-cut of highlights took far longer than I expected. I have gained new respect for the video game streamers and reviewers who make this look a lot more streamlined. But I suppose I’ll get better with practice; I intend a rematch!