Historical research continued in the form of two rematches, necessary after Evan killed me in a careless raft crash. George and I each took a turn as wagon captain; hijinks ensued.

And now we have our own Oregon Top Three:

- Taylor, Carpenter, 3270 points, 2 casualties (including Evan), good health (but only at the end…)

- George, Banker, 2199 points, 0 casualties (showoff), fair health

- Evan, Banker, 1007 points, 3 casualties (including Taylor), fair health

We even had our first case(s) of dysentery! And a question came up along the way. Clearly, one of the best gameplay features of our edition of Oregon Trail is the voiceover performance delivered by George — who at one point wondered,

I wonder if these were real people?

Yes, it turns out. Which isn’t much of a surprise considering the game’s educational aims. But while we may not meet these people on our travels west, we may just see some of the places they stopped to rest.

Marnie Stewart

Helen Marnie Stewart is quoted a few times in the game. She and her carpenter husband (See Evan, some people played as the carpenter for realsies!) traveled west after meeting in Pennsylvania. He had previously sailed through New Orleans around Cape Horn to California to mine gold, and then to Australia for a gold rush there before returning to Pennsylvania where he met Miss Stewart. Later, in 1853 when Marnie was 18, they crossed the plains in a wagon train led by Marnie’s father. Her daughter wrote:

My mother’s father, John Stewart, started across the plains with his wife and four

daughters, two of whom [including Helen Marnie, of video game fame] were married. There were over 100 wagons in their train. Some distance [east of] Salt Lake, when the wagon train was pretty well strung out, some of the wagons took the fork in the road that led to Salt Lake. […] The rest of the wagons did not notice that some had turned off, so continued the trip until it came time to camp that night. My mother’s half-sister, Mrs. James Stewart, with her family, was with the part of the train that had turned off toward Salt Lake. Her little girl, Jessie, who was seven years old, was riding with [Marnie’s mother]. This little girl didn’t see her folks again for two years, for the wagons that had headed for Salt Lake wintered there and went on the next spring to California.

After the train divided, Marnie’s parents encountered someone who claimed to have a shortcut to the Willamette Valley, which would later be known as Greenhorn Cutoff, which went toward present-day Eugene, crossing the Cascades at Summit Lake. There was a trail, but no wagon road, which slowed them down considerably.

They were almost out of provisions, their cattle were worn out, and the wagons were almost racked to pieces. Martin Blanding [went ahead] to the settlements on the other side of the Cascades and secure help. He was found at the foot of Butte Disappointment, near the present town of Lowell, almost starved to death. He told them of the emigrant train he had left and also that they had been out of flour three weeks and were very short of provisions. A settler rode all night, visiting the farmers around there, securing provisions and help to go to the aid of the stranded wagon train. [Ultimately, the emigrants were taken to Eugene.]

Interview with Jeanette Love Esterbrook, granddaughter of John Stewart done by “the Journal Man”, Fred Lockley, Oregon Journal, September 14 and 15, 1927. Collected online by Stephenie Flora.

Whitman Massacre

One of the darker pieces of dialog, which we opted not to read aloud:

With various encounters with Native tribes, Oregon Trail at least attempted to reveal some truth to the relationship between settlers and these peoples, beyond the “history as written by the victor” presented in schools at the time the game was published (and even still) — mentions of overhunting, wasteful land use, senseless violence, and disease. But the game also showed moments of cooperation, too, and how Native guides were instrumental in passing certain obstacles. But this one stuck out from the tone of most other in-game quotes.

The Whitman massacre (now referred to as the Tragedy at Waiilatpu by the National Parks Service) was the killing of the American missionaries Marcus Whitman and his wife Narcissa and eleven others near Walla Walla, Washington, on November 29, 1847 by members of the Cayuse tribe who accused Whitman of having poisoned 200 Cayuse in his medical care. Surging numbers of Oregon-bound emigrants had sought refuge at the mission — sprawling through and overhunting Cayuse-inhabited land — and brought a measles outbreak, which wiped out half the tribe by some estimates.

Adapted from Wikipedia, Cassandra Tate, NPS, and Robert Ruby.

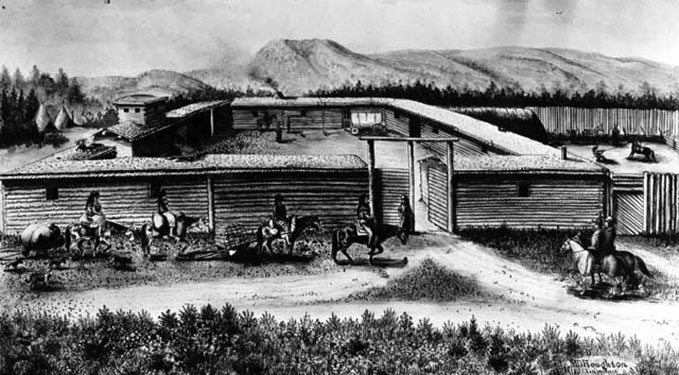

One of the eyewitness accounts comes from Mary Ann Bridger, the youngest daughter of “Mountain Man” Jim Bridger, who the game quotes as having established Fort Bridger in present-day southwest Wyoming — though a remote corner of Mexico at the time.

James Felix “Jim” Bridger & Pierre Louis Vasquez

Jim Bridger already had more than 30 years experience in the West as a trapper, mountain man and Indian fighter before he became the premier guide for the U.S. Army in the mid-1850s. In 1822, at 17, Bridger enlisted in the Ashley-Henry expedition sent from St. Louis to trap beaver in the Rocky Mountains. […] He mastered wilderness lore and accumulated an astounding mental map of western North America when nearly all of it was still unsettled by [European-American emigrants].

Wyoming Historical Society.

Bridger also built relationships with multiple Native tribes, including the Shoshone, and was even married three times to Native women. After he quit the dying fur trade, he and Louis Vasquez established a trading post in 1833 along the Green River and for the next fifteen years, ran this important post for provisions and wagon repairs for the increasing traffic of Oregon, Mormon, and California Trail settlers. His knowledge of the area and its people turned him into a lasting legend of the early American west.

[Vasquez] and Bridger sold their fort in 1858, but Vasquez already had retired to Missouri. In 1868 he died at his Westport home, and was buried at St. Mary’s Church cemetery. Years before, in 1853, Louis Vasquez gave to his good friend Jim Bridger his own rifle as a gift. From 1998 the rifle is shown at the Museum of the Mountain Man at Pinedale, Wyoming.

Wikipedia.

Perhaps I can use this as a reason to add Pinedale — my Wyoming retreat — to the map.

Celinda Hines

Celinda Hines and her whole family wrote extensive diaries. Celinda’s father died during the Snake River crossing, but according to her own diary, there was no time to mourn:

August 26: The men came & informed us of the distressing calamity of which we had heard nothing. I will not attempt to describe our distress and sorrow for our great Bereavement. But I know that our loss is his great gain… With hearts overflowing with sorrow we were under the necessity of pursuing our journey immediately as there was no grass for the cattle where we were.

August 27: Took water with us & went about 15 miles to Malheur river & camped. Road pretty good mostly through sage. Our camp was in a very pretty place but all was sadness to me.

Collected by Michael McKenzie, Ph.D.

Salty as the Platte River is…

A pair of articles from Grunge.com, Things In The Oregon Trail Game You Only Notice As An Adult and Messed Up Things That Actually Happened On The Oregon Trail, offer some insightful stories, too.

An unnamed woman [at Fort Laramie] mentions the Platte River by name, and says it’s better to drink salty-tasting water than to get cholera. That’s true, but drinking water from the Platte River was almost guaranteed to give you cholera.

According to Grunge and the Wyoming Historical Society:

From what’s now central Nebraska to South Pass in west-central Wyoming, travelers to California, Oregon and Utah all took more or less one route, including a treacherous crossing of the South Platte River where it forks in western Nebraska. So it became a crowded bottleneck.

In mid June 1847, the first Mormon pioneer party, bound for the Salt Lake Valley, built a stout ferry. As they were finishing up, they found 108 wagons from other parties, stretched over four miles and “all wanting to cross the river,” Mormon diarist Norton Jacob wrote. Ten Mormon men stayed behind to run the ferry for the rest of the emigration season. They were directed to charge non-Mormons $3 cash or $1.50 worth of provisions. This Mormon Ferry, as it came to be known, was the first commercial ferry at the upper crossing of the Platte, operating about where the bridge on Wyoming Boulevard crosses now between Casper and its suburb of Mills, Wyo.

However, the relatively salty waters of the Platte River make a very good breeding ground for cholera — which of course passes in human waste… cycling through the people waiting up and down the banks of and creeks feeding into the river.