Baker City, moreso than others we’ve driven through, has really positioned itself as The Oregon Trail City entering Oregon, so we stopped by their Centennial Obelisk and Memorial on the way out of town — which got us thinking about the date. We knew westward migration really hit its stride in the late 1840s, but it was apparently in 1843 that the first major train, nearly one thousand people, headed west.

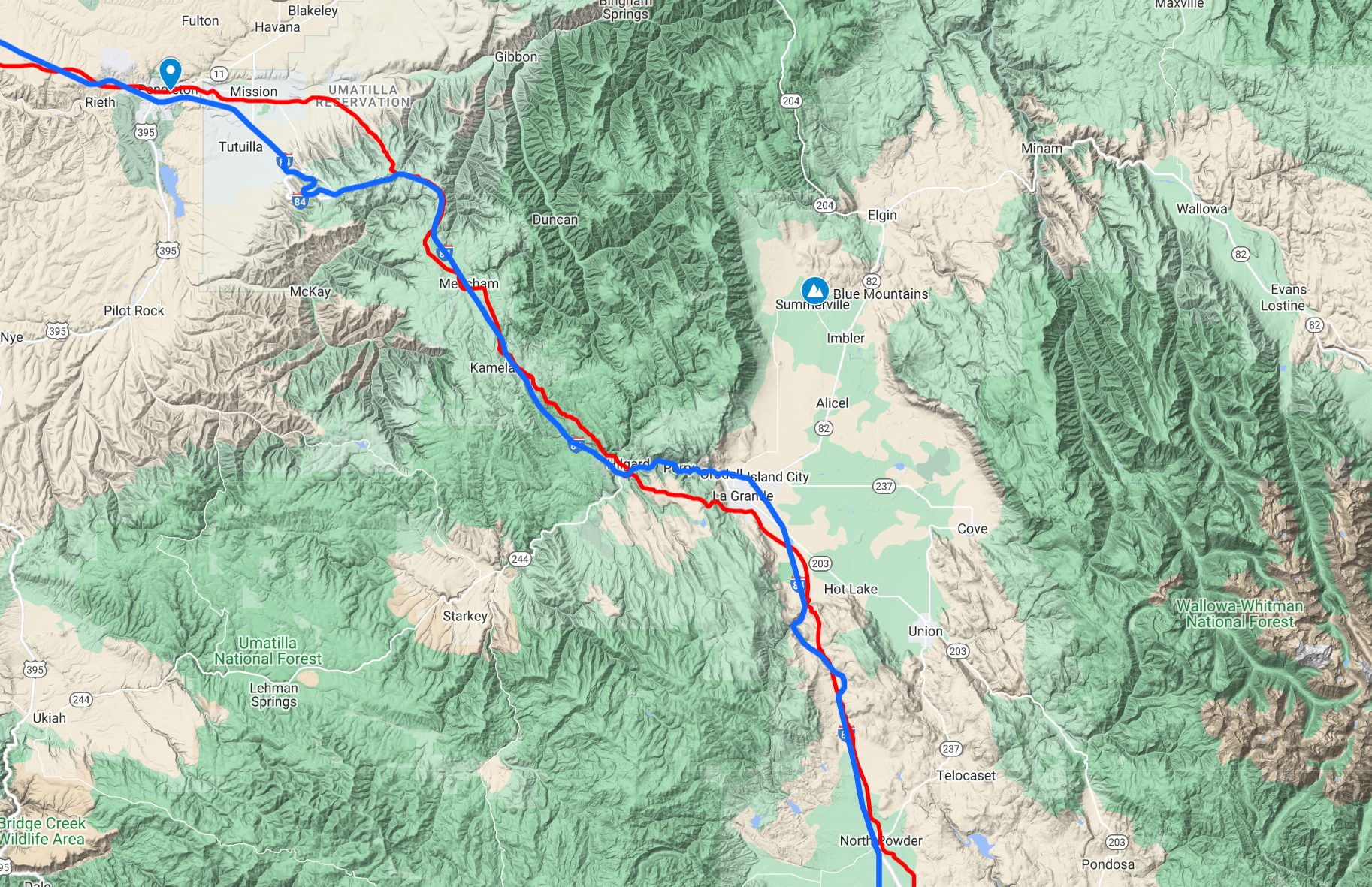

Both in western Idaho and in eastern Oregon, The Oregon Trail Scenic Auto Tour route — which we’ve tried to take when possible — actually follows Interstate 84 — which we traditionally try to avoid. But as we snaked up the mountain pass, I couldn’t help but look off to the mountains on either side to look for the fading, long-forgotten ruts braided with present-day pavement.

The Blue Mountains is the final mountain range in the trail, and while Oregon is more green and wooded than the last two states we’ve crossed, there still wasn’t an abundance of water up high.

Water is scarce in the steep, forested slopes of the Blue Mountains and is often found only at the bottom of steep ravines. Although forage for livestock is plentiful, it is widely scattered among the trees. Oregon Trail emigrants quickly discovered that livestock could not be allowed to range to free. Many along with Honore-Timothee Lempfrit, emigrant of 1848, found “Nearly all of them strayed during the night…. consequently when morning came we found ourselves without any oxen.” Although the search for lost animals was a common experience, more than livestock could be lost in the forest.

Rest area placcard placed by … some Oregon government department that didn’t sign it.

One popular camping area with a small spring is now known as Emigrant Spring, near the top of Dead Man Pass between La Grande and Pendleton.

We stopped there for a short stroll through the trees, and again on the way down the pass — at the same spot where I stopped with the Celica the night I cut through Oregon on my way north.

Hat Rock

EG found a scenic area that looked worth a detour, saving us from further Interstate-related woes. Hat Rock is a waypoint noted on the Lewis & Clark Expedition maps and sits on the auto tour route for the highway route that follows that journey. As we cut through waving wheat fields north toward Oregon 730, we caught our first glimpse of the Columbia River, which we’ll follow from here, all the way to Oregon City.

I was surprised at the lack of greenery in north/central Oregon. It is less wooded than I expected, and except for the irrigated agricultural fields, there is still a lot of desert scrub and rocky ground.

The Dalles

After Hat Rock, Oregon 730 rejoins I-84 as it speeds along toward The Dalles and eventually Portland. The headwind was shockingly intense. It felt like we’d dropped into a tunnel focusing all the Pacific Coast’s wind straight at us. We were pushing hard to go 70mph and it felt like we were going nearly 100. I developed a few new wind related whistles and rattles. On the occasional radio calls, both the Fiero and Piazza sounded as if they were on the verge of rattling to pieces. My turn signals got stuck on-solid a couple times, too — don’t let me down now, Wagon.

We finally emerged into The Dalles and headed straight to a brewery for dinner before retreating up the mountain to our swanky cabin with a view, at which we’ll camp an extra night to regain our health and resupply — as we debate the merits of our last routing decision: do we float the river or take our changes on the Barlow Road?