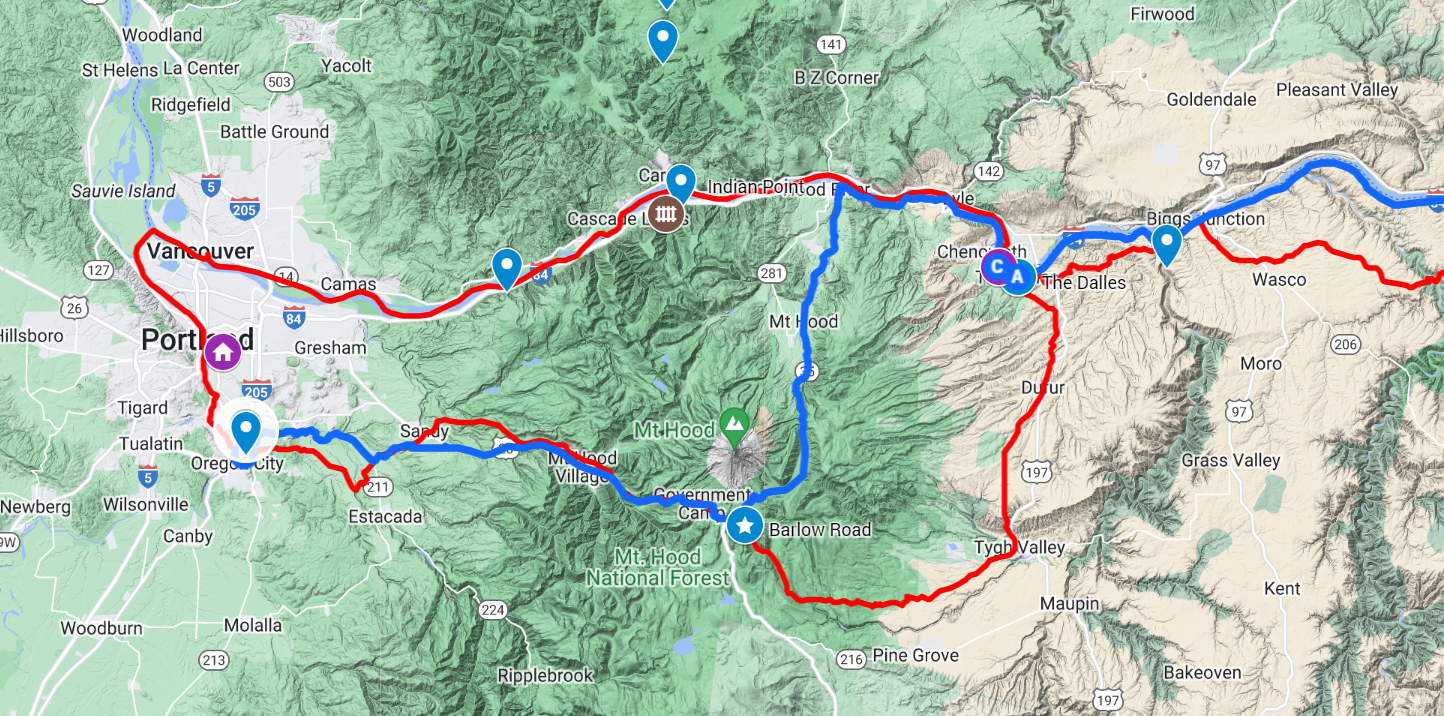

It was an odd feeling that our final drive day could be as short as an hour, should we opt for Interstate 84 through the Gorge floating the Columbia. Instead, after a leisurely morning, we packed up and headed south for The Barlow Road through the Cascades.

In truth, parts of the Barlow route directly south from The Dalles are unpaved or difficult to follow. So we took 84 to Hood River for the Mt. Hood Oregon Scenic Byway (State Highway 35) to the “Barlow Summit Trailhead” along the Pacific Crest Trail at Government Camp, Oregon.

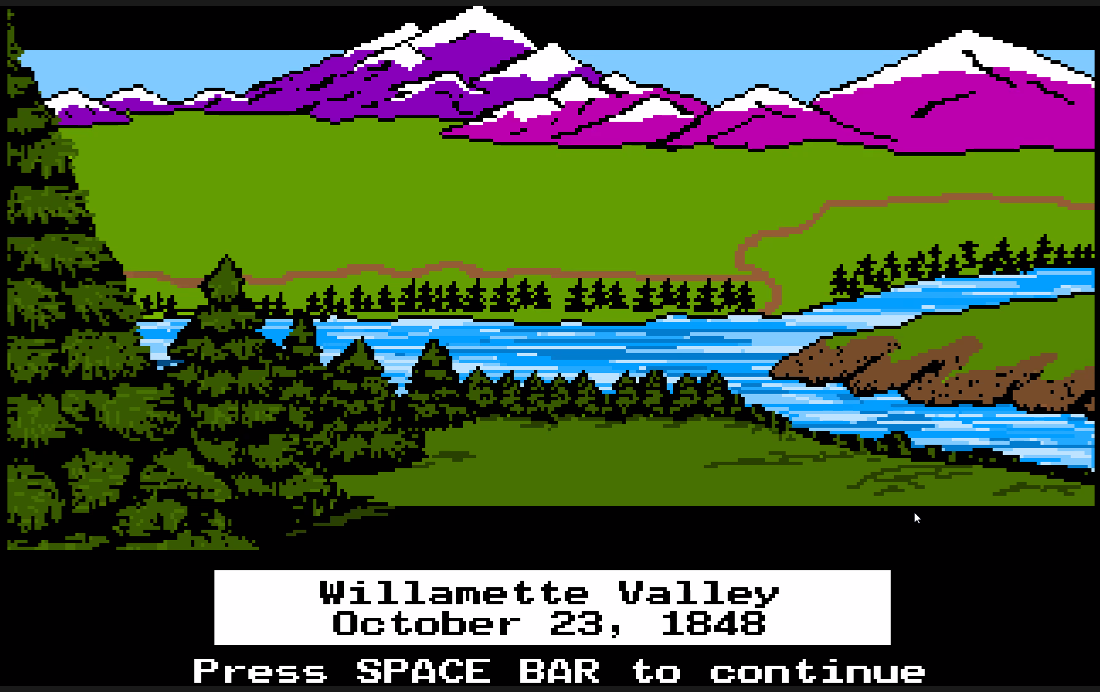

The mountain pass is named for Samuel K. Barlow who opened the first wagon route over the Cascades in 1846 to complete the Oregon Trail. The route was far from easy. Emigrant Isom Cranfill (a cabinet maker, farmer, and itinerant preacher) made the journey in 1847, [described it in his diary as] “disparate bad beyond description.”

Placcard by U.S. Forestry Service, Mount Hood.

Eleanor Allen, an 1852 Barlow Road emigrant, wrote about her misgivings near Barlow Pass: “I have thought of home, the dear ones there, the quiet Sabbath, and the sanctuary they enjoy, while we are among the cruel mountains, in the most dreary place, dependent upon strangers for assistance in getting along, nearly out of provisions and our stock famishing! All these things together almost shake the faith, but it must not be so.

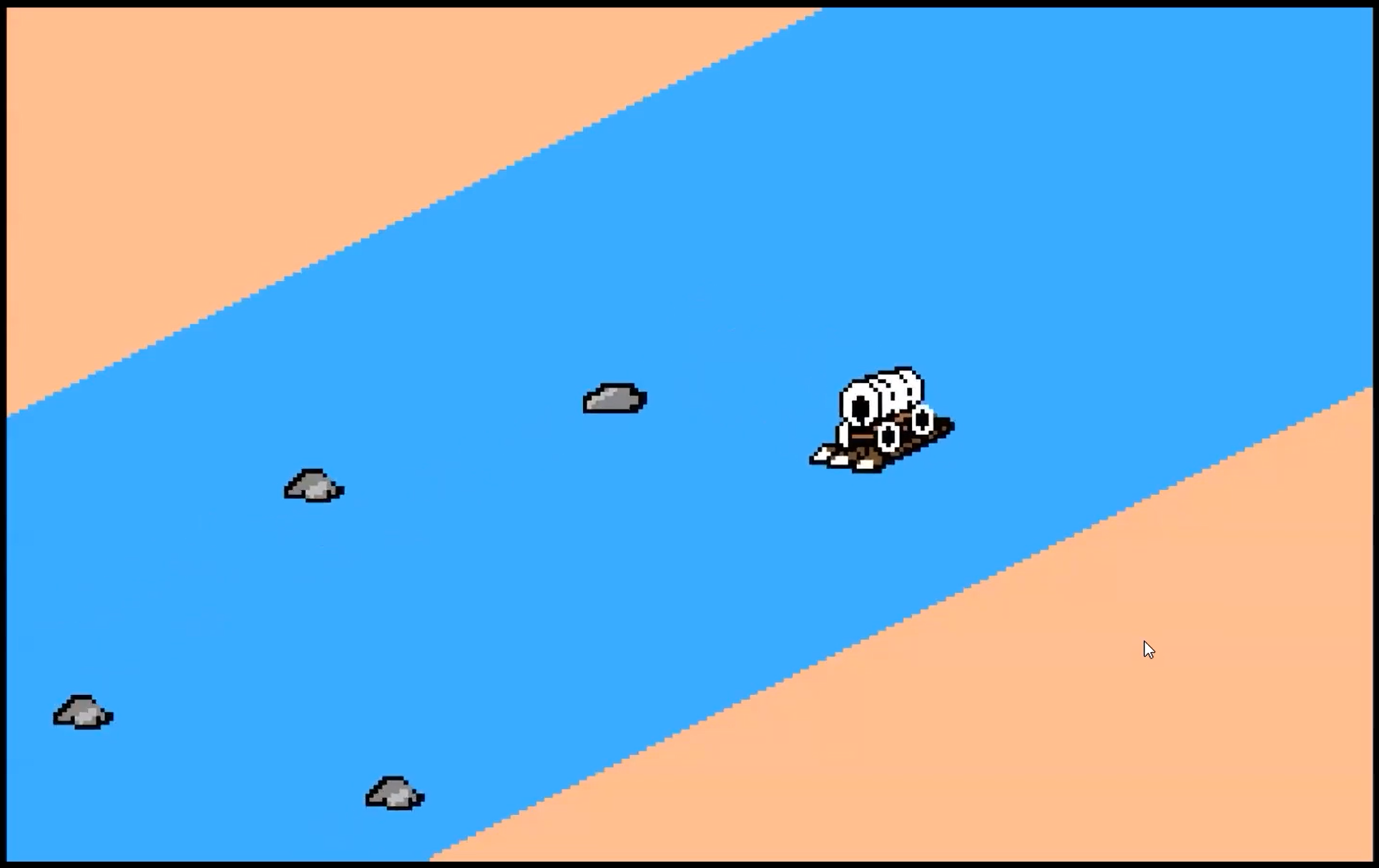

It was almost hard to remember that this area, particularly in fall, is known for its dreary, grey weather as we stood under an intense sunshine. It did get me thinking though, what was the “real” alternative — surely it’s not what the mini-game about floating the river depicted.

The west end of the gorge was wretchedly unsuitable for a wagon road: the river was hemmed in by steep slopes and cliffs of hard, volcanic rock, the climate was cold, wet, and windy, and the only areas that were reliably flat enough to permit wagons to pass were soggy bottomlands that were subject to seasonal flooding. Before 1843, no wagon had made it much past Fort Hall intact.

From 1843 until 1845, wagons could reach The Dalles, but from there the emigrants had little choice but to make a raft of pine logs, buy a raft from enterprising Indians, or rent a bateaux from the Hudson’s Bay Company for around $80. Many lives were lost on the rapids of the Columbia River, the relentless winds overturned many a raft, and there was a stretch of impassable rapids that had to be portaged. Worse still, families were often divided as cattle were driven over Lolo Pass, on the northwest shoulder of Mount Hood, to Eagle Creek and Oregon City. Despite these hardships, almost one in every four emigrants chose the river route after the Barlow Road was opened.

Final Leg of the Oregon Trail, Oregon-California Trails Association

Oh my god even that was real…

Given the Barlow Road was, indeed, unpaved — and also impassible because a bridge is out (and condemned…), we hiked along the trail for a mile to Barlow Creek and a meadow. After the stroll, we stopped at Barlow Summit along a snowmelt / glacial river for a few minutes of sun and cold air, and a little victory in the mountain air.

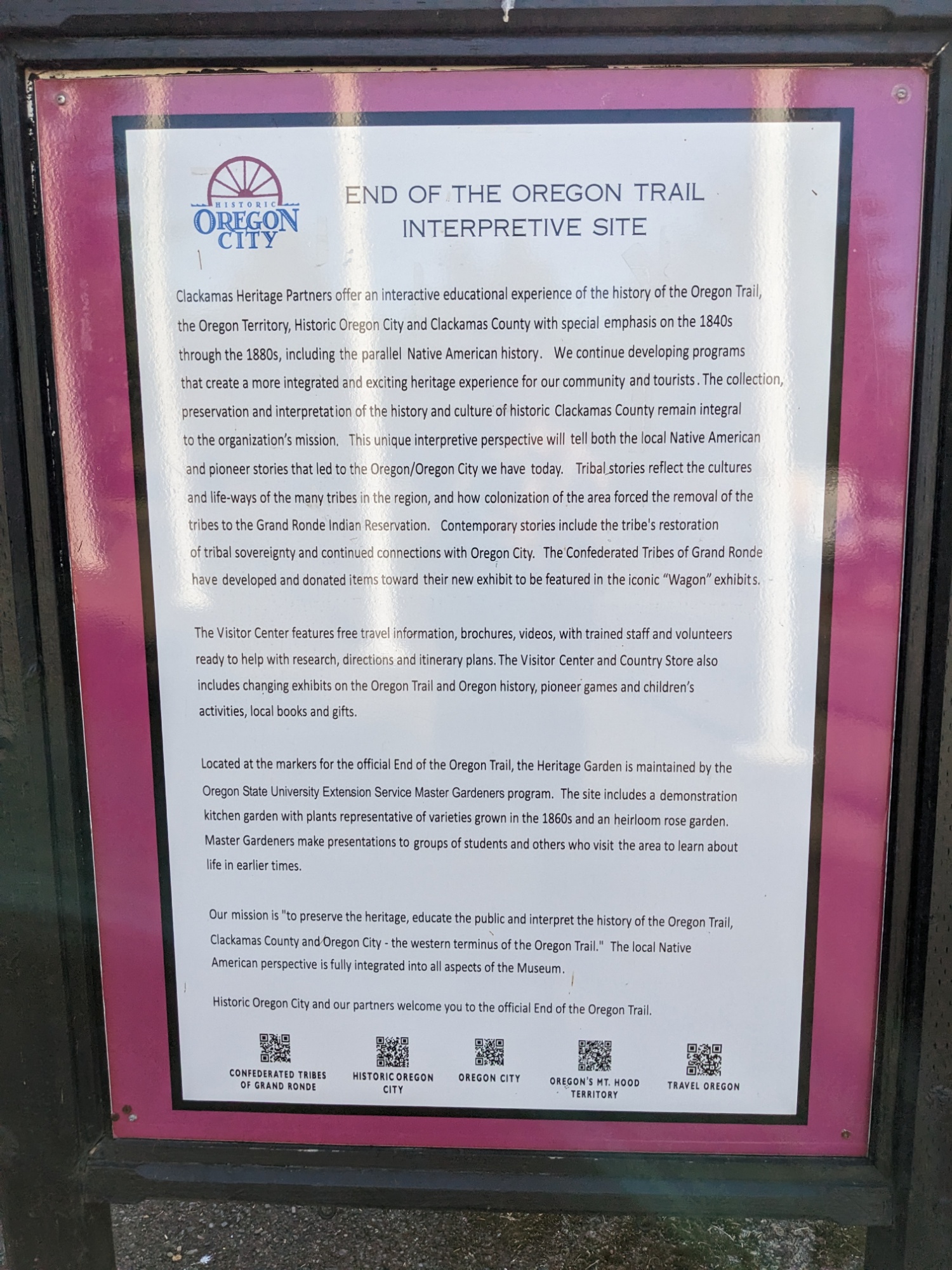

The End of the Oregon Trail [Interpretive Site]

We stopped for a celebratory beer and late lunch at the nearby Mt. Hood Brewing Company before following our scenic highway and then a treacherous rush hour snare down into Oregon City, a suburb of present-day Portland, to The End of the Oregon Trail … Interpretive Site with costumed performers and re-enactments. Thankfully, we arrived after they’d closed for the night, allowing us to quietly peruse a few placcards (which I am officially out of energy to keep reading at this point).

We made it.